We’ve read the study, and we’ve also watched the other videos flood-in from Dr Eric Berg, Thomas DeLauer, and Dr Lane Norton – where they pull the study apart and collectively point to this being a case of Reverse Causality, where – basically – the very fact that this study was based on unhealthy individuals, and that Erithrytol is produced in the body as a by-product of Glucose processing and in response to oxidative stress, they felt that the increased Erythritol displayed in people who experienced Major Adverse Cardiovascular Events, was not necessarily from exogenous sources, but from endogenous sources as a result of the body’s response to being unwell.

And they landed at this conclusion because the study did not assess or even record whether the participants were consuming erythritol exogenously – from food and drink sources – aside from the final part of the study, which we’ll explain shortly.

So, they have published a study with the fundamental message to people being – be careful about consuming erythritol, since we’ve proven that it increases your risk of heart attacks – without actually determining whether the correlation they found in their study, between elevated erythritol levels and the risk of major adverse cardiac events, was the result of the participants consuming erythritol, or whether it was the result of other factors, with erythritol levels being a result of, not the cause of, these increased risk factors.

Now, the question for us then becomes – since the study authors missed this key piece of information, and it has raised doubts about the legitimacy of the findings – how do we use the data that the study provides, team it with data from several other studies regarding erythritol and endogenous vs exogenous blood levels, and figure out for ourselves – were the participants in this study clearly consuming a lot of erythritol-laden food and drink, or were their elevated erythritol levels purely the result of endogenous production due to their unhealthy lifestyles.

We did some digging on this, and the results were eye-opening.

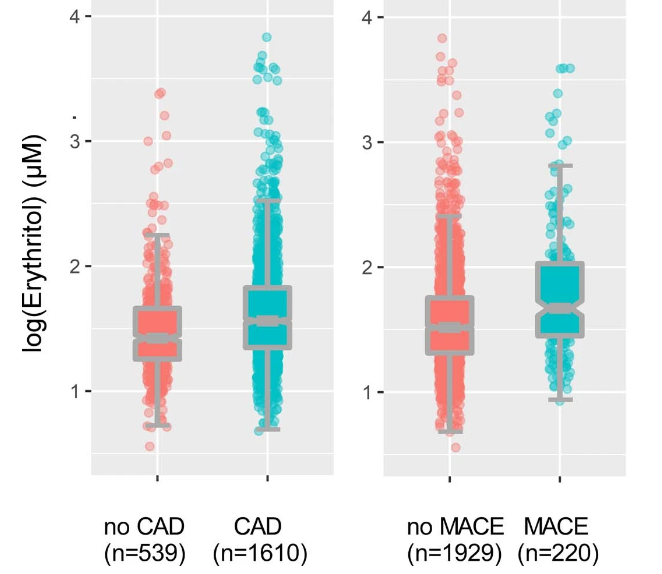

So, this recent study, titled ‘The artificial sweetener erythritol and cardiovascular event risk’ which was published at the end of February 2023, shows the baseline blood levels of Erythritol in the study participants, and split this data to show how Erythritol blood levels compared between those that suffered major adverse cardiac events over a 3-year period, and those who did not.

Those who suffered from a Major Adverse Cardiac Event over a 3-year period, had a median baseline erythritol blood level of around 1.7 micromoles per litre of blood, whereas those who did not suffer a major adverse cardiac event had a baseline level of around 1.55 micromoles per litre.

Now you might say, okay, that’s around a 9% difference. You could argue that this may be statistically relevant.

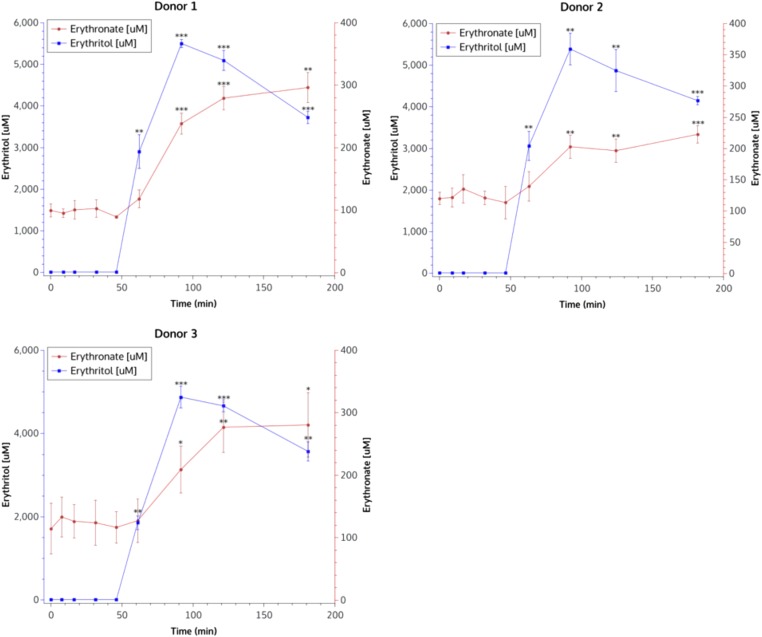

But not when you look at how an exogenous form of erythritol affects blood levels of erythritol. We found another study titled ‘Erythritol is a pentose-phosphate pathway metabolite and associated with adiposity gain in young adults’ which examined the effects of ingesting around 50g of erythritol (which, for context, is not an uncommon amount to find in the avg serving size of beverages or confectionary that use erythritol in place of sugar).

It found that Erythritol blood levels peaked around 100 minutes after initial ingestion, rising from a level close to zero (they don’t specify the actual baseline value, and it’s difficult to see this on the graph), to a huge value of 5,500 nanomoles of erythritol per litre of blood.

Now, let’s put this into context, that’s 3,235x higher than the baseline blood levels shown in ‘The artificial sweetener erythritol and cardiovascular event risk’ study.

In fact, this study itself basically confirms the drastic effect that exogenous erythritol has on blood levels of erythritol when, in the very final part of the study, they took a grand total of 8 participants, and gave them exogenous erythritol in the form of a beverage that contained 30 grams of erythritol, and noted that it increased their blood levels of erythritol 1,000 fold. Which, seems to sit in-line with the results shown in the other study just mentioned, since this was a smaller dose of erythritol at 30g, rather than the 50g ingested in the earlier mentioned study, so you’d expect a rise in blood levels of around this amount.

The study also mentioned that erythritol blood levels remain in a noticeably elevated state for 2-3 days thereafter.

So, what does this all prove?

Well, it basically proves that the vast majority, if not all, participants in this highly flawed study, were not regular consumers of exogenous erythritol – since, if they were, you’d have expected at least one or two to have consumed something with it in, within the 2-3 day window, prior to having their baseline bloods checked, and if they did, they’d flag as a very obvious outlier on the range.

But as we can see, the range only extends to around 4 nanomoles per litre in the US cohort.

With this in-mind, we’d confidently estimate that NONE of the participants in this study regularly consume food and beverages that contain significant levels of erythritol.

So the underlying message that the media have led these findings with, is HIGHLY misleading – they are basically telling people to be careful about consuming erythritol, on the basis of a study that analysed people who clearly don’t even consume it themselves.

The study is flawed in so many ways, many of which have already been thoughtfully highlighted by Thomas DeLauer, Dr Eric Berg, and Dr Lane Norton – but we just wanted to see if we could answer the ONLY thing that left a thread of credibility to this study, and that was an assumption that the participants were consuming exogenous forms of erythritol. And as we’ve just shown, they clearly weren’t.